Bass Reeves is finally getting his due in popular culture.

Original Author: Sydney Trent

Original Publications: Washington Post

Date: December 14, 2019

Ponder, for a moment, the ideal law enforcement hero for our times — an era in which Americans are increasingly aware of the role racism plays in criminal justice and the virtue of character feels far too rare.

Our idol would probably be a righteous badass, rounding up criminals by the dozens, quick on the draw but with the kind of ironclad integrity that evokes the Lone Ranger. That hero might even be African American, struggling against barriers few white men could fathom.

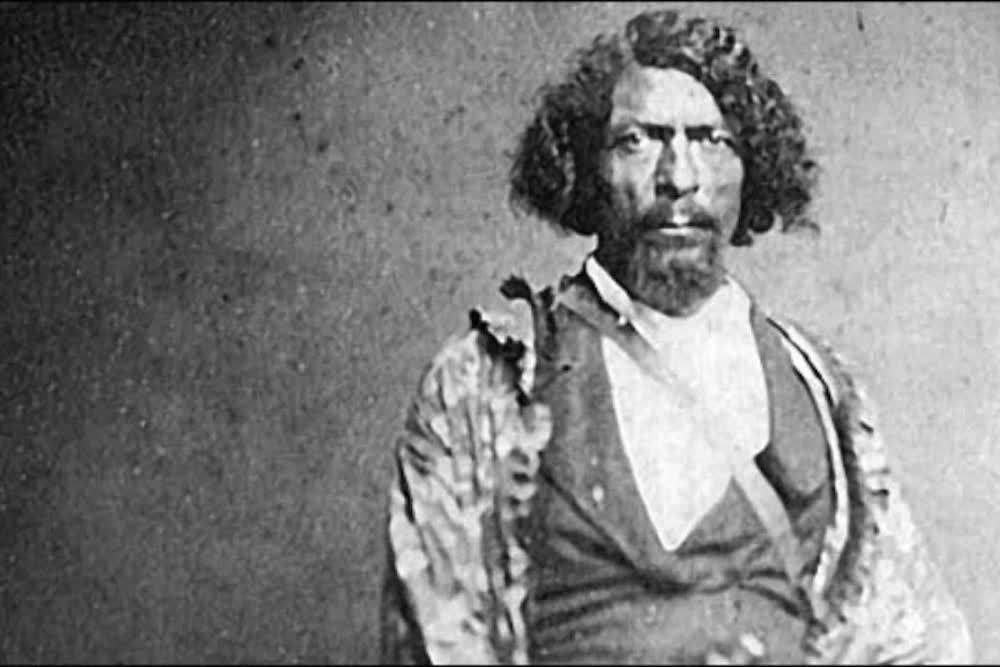

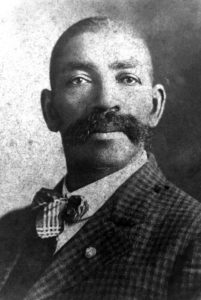

Now, popular culture has discovered such a hero. His name was Bass Reeves — a former slave and one of the first black U.S. deputy marshals west of the Mississippi. He became legendary during the late 19th and early 20th centuries for his prowess at hunting down criminals in Indian Territory.

Reeves is featured in the opening of “Watchmen,” when the black crime-fighting hero of the HBO series, Will Reeves, is shown as a boy in a darkened Tulsa movie theater captivated by the Western gunslinger shooting it out on-screen. And on December 13, 2019 “Hell On the Border,” a movie about Bass Reeves, debuted in theaters.

Reeves, a tall, burly man with a boisterous manner who reportedly handled a .44 Winchester rifle so ably he could kill a man from a quarter-mile away, brought scores of outlaws to justice, many of them white. In a turning of the tables nearly unheard of after Reconstruction, Reeves even hunted and arrested white men for lynchings and other racial hate crimes, according to Art T. Burton, 70, a retired university administrator and history professor who wrote the 2006 Reeves biography “Black Gun, Silver Star.”

Burton himself is of Western stock, from a family of black Oklahoma cowboys. “You didn’t see black cowboys in movies and television,” he said. “At first I just thought my relatives were strange.” When he was 11, Burton recalls, an uncle mentioned that there were a lot of black gunslingers in the West, and he became, like the fictional Will Reeves, captivated by that prospect.

Thus began the author’s personal manhunt for a black cowboy who had made a name for himself. Bass Reeves kept surfacing, in the stories of old black Oklahomans and later from the owner of a black Western museum in Denver. Outside of Western African Americans, however, Reeves’s extraordinary life appeared nearly lost to history, said Burton, who later unearthed numerous old newspaper articles that described Reeves’s escapades in surprisingly fawning prose.

Those exploits began during the Civil War when Reeves, who had been born into slavery in Arkansas, fled his post as his master’s body servant during battle. He made a new life as a runaway in Indian Territory, which became part of the new state of Oklahoma in 1907. There, he probably fought for the Union, Burton said, and learned the ways and languages of the Chickasaw, Creek, Cherokee, Choctaw and Seminole tribes. The Five Civilized Tribes, as they were known at the time, had been pushed onto the Territory by the 1830 Indian Removal Act under President Andrew Jackson.

Reeves’s code-switching talents — as he deftly negotiated the multicultural territory while working alongside mostly white U.S. marshals as a sharpshooting posseman — caught the attention of the U.S. Marshals Service, which hired Reeves in 1875.

He worked under Judge Isaac Parker, the famous “Hanging Judge,” who presided between 1875 and 1896 over the U.S. District Court for the Western District of Arkansas in Fort Smith. At one time, it was the largest criminal court in the country.

The marshals were tasked with hunting down bad guys in Indian Territory who were beyond the reach of tribal law, which extended only to tribal members. By the start of Parker’s tenure, the wide-open territory had become a haven for dangerous fugitives eager to take advantage of jurisdictional loopholes.

The star on Bass Reeves’s chest, along with the Colt pistols on his hips, conferred authority. But his life was still circumscribed by racism, even in a place where tribal members, black and white settlers and “Indian Freedman,” or the former black slaves of Native Americans, mixed with relative freedom.

At one point, Reeves was unsuccessfully tried for murdering a black cook under charges that Burton writes would probably not have been brought against a white lawman given the same circumstances. Like many slaves, Reeves had been forbidden from learning to read. Instead, he memorized the way suspects’ names appeared on paper, then matched them with the way they sounded so he could serve arrest warrants and subpoenas.

Like most people, he had his struggles. He was married twice, fathered one of his 12 children out of wedlock and possibly suffered from post-traumatic stress disorder from his time on the battlefield, Burton said. Yet he was also a brave truth-teller who was gentle with animals and so revered the law that he reportedly served an arrest warrant for murder to his own wayward son.

His productivity over the 32 years he served before he retired in 1907 was remarkable.

“Reeves would round up dozens of outlaws at a time — 12, 15, 16 — while most deputy marshals brought in four or five at a time,” said Burton, who makes a compelling case that Reeves was the inspiration for the fictional Lone Ranger.

Newspaper accounts from the time celebrate the frontier lawman’s skill.

“Bass Reeves is the most successful marshal that rides in the Indian country,” declared a story in the Daily Arkansas Gazette in 1891. “He is a big ginger-cake colored negro, but is a holy terror to the lawless characters in the west. … It is probable that in the past few years he has taken more prisoners, from the Indian Territory, than any other officer.”

Reeves played a role in the capture of some of the most famous fugitives in the territory, including the Seminole outlaw Greenleaf and Bob Dozier (Dosser by some accounts), a prosperous farmer turned criminal who evaded authorities for years before Reeves cornered him in a ravine and killed him with a bullet to the neck. The hunt, based on oral history, plays a central role in the new movie.

The newspapers, as well as court testimony contained in Burton’s book, detailed Reeves’s role in apprehending whites who had committed crimes against African Americans, even if the charges sometimes amounted to nothing. He rounded up instigators of a race war, according to a news account, and caught hell for lugging around two white men in a prison wagon for two months after they were accused of murdering a black man, according to Burton.

But the tale that Burton said best illustrates his view that Reeves was “a man of a different kind” happened in 1899. In what became known as the “Wybark Tragedy,” Ed Chalmers, who was black, and Mary Headley, his white common-law wife, were murdered by a white mob.

One of the suspects was a man named William “Cap” Lamon, an affluent landowner who owned two cotton gins, Burton said. Bass Reeves was the lead investigator on the case and, according to an oral history obtained by Burton, sneaked up on Lamon in his cotton fields to make the arrest. Although Lamon was eventually let go, “for a black man to apprehend a white man on his own property was remarkable for that time,” Burton said.

By the time Reeves died in 1910 at the age of 71, the leeway he and other black marshals had been granted to enforce the law in the Indian Territory had faded. In 1889, millions more acres were opened to settlers, and after Oklahoma achieved statehood in 1907, Jim Crow laws put an end to the easy mingling of African Americans with people of other races.

In 1921, the Tulsa race riot, one of the deadliest in U.S. history, destroyed the culturally and economically vibrant black neighborhood of Greenwood.

Burton believes the strident racism of the Jim Crow era and ensuing decades obscured the horrors of the riots, just as they nearly extinguished what was known of Bass Reeves’s remarkable life.